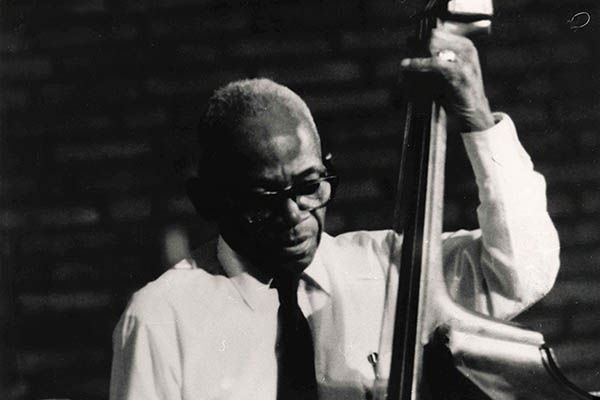

An initial idea to write, now legendary, article New Orleans String Bass Pioneers, that came out in December 1990, Daniel Meyer had when he was doing research on Chester Zardis. Written just a couple of months after his passing, this article was originally published in New Orleans music magazine Wavelength #121 in November 1990. Mr Meyer was kind enough to let us republish it for our readers here at Art of Slap Bass.

CHESTER ZARDIS

by Dan Meyer

He was 90 when he died this year, but even up to his death, oh, how he could slap that bass!

Chester Zardis Sr. died in New Orleans, the town of his birth, on August 14, 1990. The distinguished jazz bass player was born on the 27th of May, 1900. Most people would say that 90 years is a fine age to live to; however not so long ago Mr. Zardis was playing the string bass with such youth and vigor that those of us listening to him hoped to hear him for years to come.

He was a short man playing a large instrument who looked as if he’d have to use a step stool to reach the tuning pegs. But, oh, how he could slap that thing! First class, house rocking, authentic New Orleans jazz string bass, did he play.

Chester’s mother did not want any of her seven sons taking to music. Musicians were good-for-nothings, she would say. But Chester managed to fool his mother by becoming a musician behind her back.

In his early teens Chester Zardis took string bass lessons from Billy Marrero, an established musician some 25 years Zardis’ senior. Young Chester had been impressed by Marrero’s performance with the Superior Orchestra; “Mr. Billy played so much bass I got swimming in my head.” Marrero sold Zardis a used bass for $5 and let Zardis keep it at his house so Mrs. Zardis wouldn’t know.

An argument at the Ivory Tower Theater with a watchman who accused Zardis of throwing a piece of paper off the movie-house balcony resulted in a fight that landed young Zardis in the Jones Waif’s Home. Zardis said he spent a good amount of his free time at the correctional work house jamming with a fellow waif who was learning to play cornet – Louis Armstrong. Mrs. Jones always said that Chester was such a nice boy that he didn’t belong in the home, and he was out within the year.

From Alan Lomax Archive

At the age of 16 Chester Zardis got his first professional job with the Merrit Band. One of these early jobs brought Zardis to the attention of banjo player Buddy Manaday, who invited Chester to join the band of cornet hot shot Buddy Petit. (Petit never recorded, but those who heard him rank him with Louis Armstrong, King Oliver, and Freddie Keppard as one of the all-time great New Orleans horn men. Some say the best). Buddy Petit, dedicated to hard drinking and wild living, was the type of musician that Mrs. Zardis was thinking about when she warned her sons about the musical life. Chester joined Buddy Petit’s Black & Tan Band, one of the area’s most popular and sought-after groups, playing regularly around town, up at Spanish Fort, and across Lake Pontchartrain. For a while Chester’s mother still did not know that he was a musician! One day, however, the band played at Perseverance Hall for the Ladies Of The True Friends, of which his mother was a member. Chester waited until the band started playing to take his position at the bass. When his mother saw him she was furious, shaking her finger at him throughout the set.

At the end of the set Chester came down off the stage and hugged his mother, explaining to her that he was incapable of staying away from music, but would be a good boy anyway.

Like many bass players of the time, Zardis played string bass indoors for dances and tuba in the street for marching bands. Little Chester would sometimes be seen carrying both a string bass and a tuba to a job, one in each arm. (Years later his doctor advised him to give up tuba for health reasons. Chester outlived the doctor). Zardis remembered exchanging bass technique ideas with Pops Foster. In one cutting contest Zardis blew Foster away by snapping the bass strings with the butt of his bow. This trick won Zardis some acclaim, but he had to give it up because it too frequently resulted in broken strings.

Chester Zardis eventually tired of Petit’s irresponsible behavior. It was Petit’s habit to book multiple gigs for the same time and simply not show up. Zardis feared this practice would eventually get him beat up or killed, so he left for the band of Petit’s rival, Kid Rena.

Chester Zardis, at this time nicknamed “Lizard”, played regularly with Kid Rena’s band throughout the 1920s, including playing bass horn in parades. Around this time Zardis also played with such New Orleans jazz luminaries as the A. J. Piron Orchestra, Jack Carey, Punch Miller, Chris Kelly, Kid Howard, Fate Marable’s Riverboat Orchestra, and was frequently drawn back to play gigs with Buddy Petit until the latter’s death in 1931.

The young bass player was much in demand; “Whatever band had the work, that’s the band I worked with,” Zardis recalled. He made his first recordings with Kid Rena’s band in 1930, records which were never issued and are presumed lost.

Zardis traveled around the country in the 1930s. He played with Duke Dejan’s Dixie Rhythm Band on the S.S. Dixie. A trip to New York resulted in a two-week stint sitting in with Count Basie’s band; Zardis said he turned down Basie’s offer of a permanent position. Zardis spent some 7 or 8 seasons working with Fats Pichon on the S.S. Capital, plying the river between New Orleans and St. Louis. Pichon lead a tight band, all dressed in white tuxedos. The band consisted mainly of reading musicians, but Chester’s good ear and great musicianship made up for his slow reading. It was Pichon who gave Zardis, then with a hefty 180 pounds on his short but powerful frame, the nickname of “Little Bear.”

The early 1940s saw the start of the national jazz revival. “Little Bear” provided rhythmic backing for early recordings by Bunk Johnson. George Lewis, and Kid Howard. World War II resulted in a stint in an Arizona army base, after which Zardis took a job as a civil sheriff. After deciding that pursuing armed criminals was not the life for him, he returned to music, traveling to Colorado and Philadelphia before returning to New Orleans in 1951. He played with Andy Anderson until retiring from music in 1954. Chester Zardis decided to spend his retirement on a farm near New Iberia, picking up his bass only to play along to music heard over the radio. When Zardis visited New Orleans in 1965, clarinetist Louis Cottrell talked him into coming out of retirement and moving back to the city.

Chester Zardis was soon working steadily again. He performed regularly at Preservation Hall, playing with the likes of George Lewis, Billie & Dee Dee Pierce, Percy Humphrey, and Sweet Emma Barrett. He toured widely with other musicians from the Hall; 90 days in Japan with Kid Sheik were followed by a tour of Europe. On a trip to Little Rock to play for Arkansas governor Winthrop Rockefeller at the opening of the John Reid Jazz Collection at the Art Museum, Zardis commented on the changes from the bad old days of segregation: “In my younger days they wouldn’t let me in a building like this.”

The 1970s and 1980s continued to be busy for Chester. He went on repeated tours when not performing around town at Preservation Hall, the French Market, the Maple Leaf, and the Palm Court. As in his youth, he played frequent jobs north of the lake. He gained increasing recognition, being featured in national and international television and radio shows.

Chester Zardis played on many of the best traditional New Orleans recordings of the last three decades. He recorded both with his contemporaries and younger musicians. Zardis’ last decade saw him frequently teamed up with a musician over half a century his junior, clarinetist Michael White. Professor White would sometimes have Chester Zardis talk and play for his jazz history class at Xavier University. Michael White especially remembers performing with Zardis at Penn’s Landing in Philadelphia about three years ago. A granddaughter of Chester’s who had never heard him play was in the audience, and Zardis went all out. “He was playing incredible stuff— sounded like drum rolls on the bass.” This was exceptional, for Chester Zardis was not a show-off. His main concern was always with the ensemble. Within this confine, however, he still managed to generate creative jazz. He had a great sense of time and syncopation, and was very concerned with tone. He played lines that almost made countermelodies, and was always ready with an appropriate fill. Michael White notes the “intense spiritual presence” of Zardis’ playing. “He was the strongest foundation you could find. He taught me a lot about rhythm, drive, and ensemble playing.”

In his final years Zardis was sometimes frustrated by the decreasing number of musicians performing in the traditional manner. He felt that drummers who played in bop or R&B-influenced styles impaired the classic New Orleans ensemble rhythm. On the other hand, when he hit it off with his idea of a good group, Zardis would be so happy he would talk about it for days afterwards.

Chester Zardis was very serious about his music, and felt lucky to be able to make a living doing what he loved. He would soak his hands in salt water to keep his fingers hard. He kept his bass set in the old fashion way, with the bridge lifting the strings high off the fingerboard. When steel bass strings came out he weighed their pluses and minuses and decided on an arrangement of two steel strings and two gut strings, which he maintained for the rest of his life. He was able to get such a loud sound out of the instrument that listeners sometimes thought the instrument amplified; Zardis recalled with amusement people coming up during breaks at Preservation Hall, looking for his nonexistent electric pick-up. Chester Zardis had a clear idea of an ensemble type of jazz which was already scarce in his later years. He would set the foundation without getting in the way of the other musicians. He would drive the band with a great swing, although Zardis’ mode of play predates what is known as the “swing” era. You can often hear the influences of this style in other bass players, but Zardis presented a rare chance to hear the style itself. As Dr. White notes, Chester Zardis was “one of the strongest links New Orleans jazz had to its past.” That link has now joined jazz history.

Thanks a lot for all these articles. You’re doing an amazing job on this site and as a young musician it’s very helpfull !!! Thanks for sharing all this knowledge it feeds the soul, the brain the heart and of course it feeds our music.

I hope you’ll have time to keep goin this way.

Big thanks and best regards from France.

Alex

Hi Alex,

comments like yours inspire us to keep it going!

There are lots of articles coming. Keep an eye on the site!

I saw that exact band at Preservation Hall in 1971 & 1972. The only difference was Willie Humphrey rather than George Lewis. Zardis played facing the wall so as to use the corner as an amp. He was amazing. The crowd would whoop at his syncopations.